- Home

- Think Pieces

- Interpersonal Dynamics

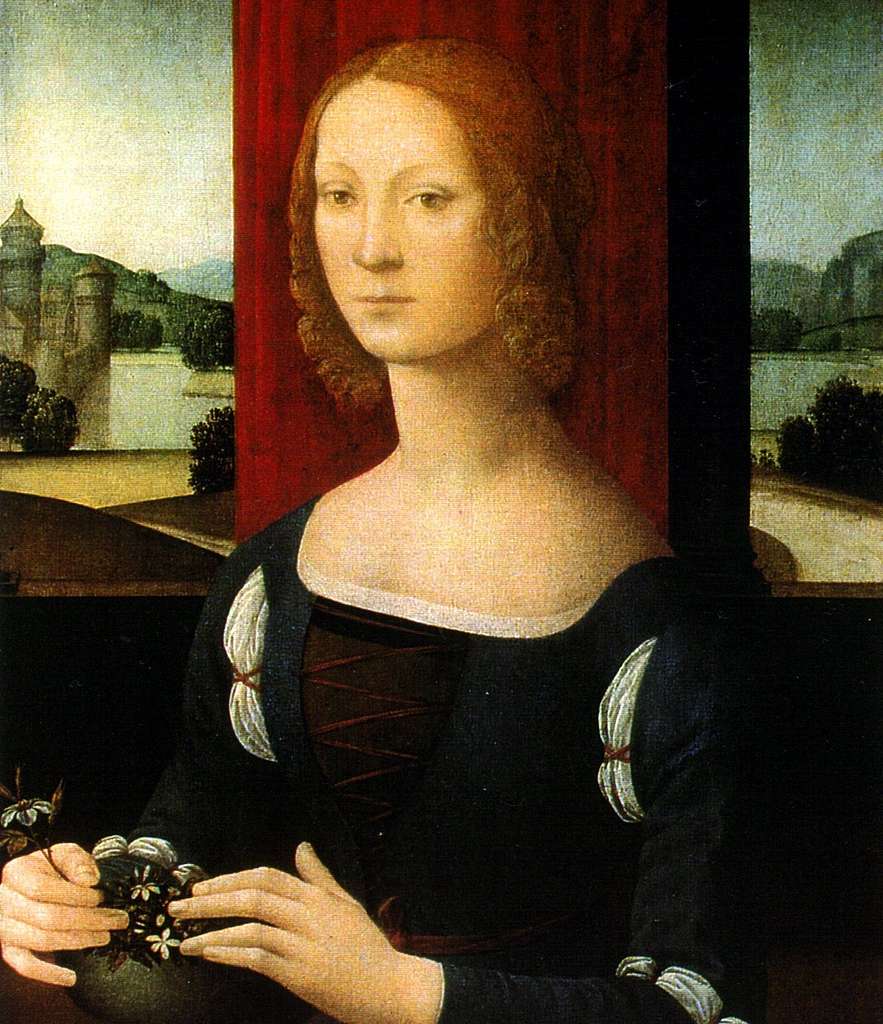

- Caterina Sforza Giacomo Feo

A Story of Risking it All for Love: Caterina Sforza and Giacomo Feo

We rarely imagine that our choices in love could lead to our downfall. Here's the poignant story of Countess Caterina Sforza and Giacomo Feo.

"The countess had spent her whole life mastering her emotions and subordinating her personal interests to practical matters.

Suddenly feeling herself overwhelmed by Giacomo’s affection, she lost her habitual self-control and fell hopelessly in love."

- Robert Greene - The Laws of Human Nature.

In The Laws of Human Nature, Robert Greene explains that as humans, we like to believe that we are rational creatures who make decisions based on what makes the most sense.

We believe that we know ourselves well, and are therefore able to use our free will in a way that will benefit us the most.

However, there is one area of life where these ideals are easily shattered - when we are in love.

When we are in love, we fall prey to emotions that we cannot control.

This leads us to doing things that eventually seem silly to us in hindsight - things such as making choices of partners that we cannot rationally explain.

Often, these choices end up being unfortunate. They cause us untold pain and suffering that we could theoretically have avoided if we were in our right mind.

When we make poor decisions in the throes of love and passion, we like to tell ourselves that a temporary madness overcame us.

We think of such moments as representing the exception, not the rule, to our character.

However, Greene argues that when we fall in love, we are actually being more ourselves.

He explains that in our conscious day-to-day life, we are sleepwalking, unaware of who we really are. We present a front of reasonableness to the world, and we mistake the mask for reality.

However, when we fall in love, the mask slips off.

We wake up to the reality of the essential irrationality in our nature.

We start to see that there are deeply unconscious forces that control many of our actions.

Although there are countless stories that demonstrate human proclivity towards irrationality when in love, the story of Caterina Sforza and Giacomo Feo stands out as a striking example.

Before Giacomo: The Background of Caterina Sforza

Caterina was a member of the powerful Sforza family, which ruled Milan continuously in the second half of the 15th century and for brief periods in the early 16th century.

She was the daughter out of wedlock of Lucrezia Landriani, a Milanese noblewoman and Galeazzo Maria Sforza, who became Duke of Milan upon the death of his father in 1466.

New to power, the Sforzas developed the practice of enrolling their daughters in rigorous training as a way to toughen them up and make them fearless—important qualities to have as marriage pawns.

As a result, Caterina was well-educated. She was also trained in fighting, horseback riding, and hunting, which was unusual for a noblewoman of her time.

When Caterina was ten years old, she was betrothed to Girolamo Riario, the crude and lustful thirty-year-old nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, a marriage that would forge a valuable alliance between Rome and Milan.

The Fearless Countess of Forlí

Riario, who was hated by his subjects, was the target of several assassination attempts and was plagued by illnesses. In 1488, a noble family in Forlì successfully arranged Riario’s assassination.

They also took Sforza and her children hostage, ordering her to persuade the soldiers at Ravaldino - Forlí’s main fortress - to surrender.

The assassins marched Caterina up to Ravaldino. She was to order Tommaso Feo - the castle’s commander - to surrender it to the assassins.

Caterina had gotten word to Tommaso before she was captured that he should resist all pleadings for surrender.

When the assassins took her to the fortress to negotiate again, she tricked them into letting her enter the castle alone. Once inside, she refused to surrender the fortress.

The captors were angry with Sforza’s trickery. The next day they returned to the castle with her six children and called Caterina to the ramparts.

With daggers and spears pointed at them in the most menacing fashion, and with the children wailing and begging for mercy, they ordered Caterina to surrender the fortress or they would kill them all.

At this, Caterina shouted down: “Do it then, you fools! I am already pregnant with another child by Count Riario and I have the means to make more!” at which she lifted her skirts, as if to emphasize her meaning.

Caterina had foreseen the maneuver with the children and had calculated that the assassins were weak and indecisive—they should have killed Caterina and her family right after assassinating the Count.

Now they would not dare to kill them in cold blood: the assassins knew that the Sforzas, on their way to Forlì, would take terrible revenge on them if they ever did such a deed.

She didn’t care what they thought of her as a mother. She had to keep stalling. To emphasize her resolve, after refusing to surrender, she had the cannons of the castle fire at the Orsi palace.

Ten days later a Milanese army arrived to rescue her, and the assassins scattered.

As all that she had done—and what she had yelled down to the assassins from the ramparts of Ravaldino—spread throughout Italy, the legend of Caterina Sforza, the fearless warrior countess of Forlì, began to take on a life of its own.

Caterina Falls in Love with Giacomo

Within a year after the death of her husband, the countess had taken a lover, Giacomo Feo, the brother of the commander she had installed in Ravaldino.

Giacomo was seven years younger than Caterina and had served the Riario household for years as one of Girolamo’s (Caterina's first husband) stable grooms.

Giacomo was the polar opposite of Girolamo; young, handsome and athletic, although little-educated and coarse of manner.

Most important, he not only loved Caterina, he worshipped her and showered her with attention.

The countess had spent her whole life mastering her emotions and subordinating her personal interests to practical matters.

Suddenly feeling herself overwhelmed by Giacomo’s affection, she lost her habitual self-control and fell hopelessly in love.

Things Start to Go Awry

Giacomo was, perhaps, Caterina’s first real love, and her passion for him drove her to make some critical mistakes.

First, Caterina made Giacomo the new commander of Ravaldino.

Caterina had him knighted, and in a secret ceremony they married.

As her lover could not leave Ravaldino, Caterina spent much of her time inside the fortress grounds, where she devoted hours to her other passion – gardening, and experimenting with creating herbal remedies and cosmetics.

At the same time, Caterina increasingly handed over to Giacomo governing powers of Forlì and Imola, and began to retire from public affairs.

She passed over the warnings of courtiers and diplomats that Giacomo was out for himself and was in over his head. She did not listen to her sons, who feared Giacomo had plans to get rid of them.

She ignored all the warning signs: the public resentment, the thwarted conspiracies, her diminishing reputation.

In her eyes, her husband could do no wrong.

Then one day in 1495, as she and Giacomo left the castle for a picnic, a group of assassins surrounded her husband and killed him before her eyes.

Caught off guard by this action, Caterina reacted with fury. She rounded up the conspirators and had them executed and their families imprisoned.

In the months after this, she fell into a deep depression, even contemplating suicide.

What had happened to her over the past few years? How had she lost her way and given up her power?

The answer is simple: Caterina Sforza had become a fool for love.

We're Not Much Different Than Caterina

Caterina's story highlights the sort of crippling weakness that we all universally succumb to when in love.

Make no mistake: Caterina was a strong, powerful woman.

When plague struck Forlì, she comforted the sick, at great risk to her own life.

She was willing to suffer the worst conditions in prison to safeguard the inheritance for her children, a rare act of self-sacrifice for a person of power.

At the same time she was a shrewd and tough negotiator. In conflicts, she always strategized to outwit her aggressive male opponents and avoid bloodshed.

This ability to play many different roles, to blend the masculine with the feminine, was the source of her power.

The only time she relinquished this was in her marriage to Giacomo Feo.

When she fell in love with Feo, she was in a highly vulnerable position.

The pressures on her had been immense—dealing with a difficult marriage, surviving the numerous pregnancies that had worn her down, holding together the tenuous political alliances she had built up.

In 1491, with Girolamo dead and her control over her dominions secured, Caterina finally got a taste of freedom.

And so suddenly experiencing Feo’s adoring attention, it was natural for her to seek a respite from her burdens, to relinquish power and control for love.

And in Giacomo, she found a lover who desired and adored her in a way Riario never had.

She became – perhaps understandably – too caught up in her passions.

Having finally found domestic happiness, she made the mistake of taking her eye off the bigger picture.

In the process she lost all initiative and paid the price, experiencing a deep depression that nearly killed her.

The Lesson

One might look at Caterina's story and wonder how she could have lost control.

Yet there is a part of all of us that can relate to her behavior.

As adults we feel relatively mature and practical, but in love we can suddenly regress to behavior that can only be seen as childish.

We are all capable of acting completely irrationally when in love.

We also experience fears and insecurities that are greatly exaggerated.

We feel terror at the thought of being abandoned, like a baby who has been left alone for a few minutes. We have wild mood swings—from love to hate, from trust to paranoia.

Normally we like to imagine that we are good judges of other people’s character.

Once infatuated or in love, however, we mistake the narcissist for a genius, the suffocator for a nurturer, the slacker for the exciting rebel, the control freak for the protector.

Others can often see the truth and try to pull us of our fantasies, but we won’t listen.

I've written before about the importance of training your mind to be stronger than your feelings.

Here's the thing:

We can't always see clearly when in love, but we can listen to those who can.

Knowing that love affects us the way it does, we can decide to listen to the warnings and advice of those who can see more clearly than us, even if what they're saying is not what we want to hear.

If you have friends and family who love you and have your best interests at heart, you are very lucky.

Listen to them.

These dear souls can provide clarity when our vision is all fogged up by the rose-tinted glasses we don when we're in love.

Thanks for reading! If you liked this content, share with a friend:

Recent Articles

-

5 Subtle Habits That Quietly Transform Your Life Over Time

Jan 25, 26 08:21 PM

Progress towards the things that matter isn't usually loud or dramatic. Here are 5 subtle habits that quietly transform your life over time. -

Inner Work with Marcus Lynn | How to Make Change More Realistic

Jan 19, 26 06:24 PM

In this spotlight interview, therapist Marcus Lynn explains how we can begin to see emotions as information and make change more realistic in our lives. -

7 Best Personal Development Courses to Grow Your Skills and Mindset

Jan 01, 26 11:04 PM

To reach your goals for the year, there are are certain skills you might need to unlock first. Here are the best personal development courses to level up your life in 2026.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.